By ROBYN JENSEN

Special to Saskatchewan Dugout Stories

While embodying the title of “Mr. Baseball,” Willie “Curly” Williams left an indelible mark on Alberta and Saskatchewan.

He earned this esteemed title from Lloydminster Meridians owner Slim Thorpe, a testament to his revered status within the baseball community. An African American and former seasoned Negro League player hailing from the United States, Williams found solace and acceptance in the warm embrace of Western Canadian baseball fans.

Particularly enchanted by the hospitality of Lloydminster, a border city that he called home for eight summers, Williams described it as a “breath of fresh air” (Swanton and Mah). This refuge was a stark contrast to the oppressive conditions he faced in the United States due to segregation and Jim Crow laws. To the bat boys in Lloydminster who diligently shined his shoes and washed his socks, they were unwittingly part of poignant irony, unaware of the stark realities Williams had left behind in his homeland.

He did have challenges on the prairies, which he would overcome in 1961 after becoming the manager of the Lloydminster Meridians. Despite the unexpected twists and turns that characterized the year, his leadership and motivational abilities became evident, ultimately leading him and the players to transition to three different teams that season.

Williams’ Negro League career & the realities of Jim Crow

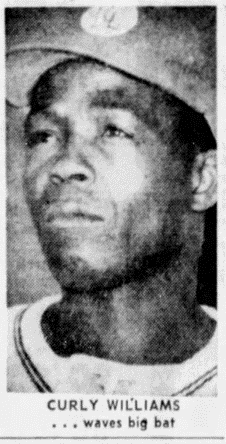

Williams, born in the 1920s, was the youngest of seven children who grew up in the heavily restrictive and segregated state of South Carolina. He never knew his father, who passed away when he was just six months old. As a boy, he turned to sports, which taught him valuable life skills extending beyond the field, such as teamwork, leadership, reliance, discipline, and perseverance. Williams was on the path to a bright career, a fact affirmed by The Times and Democrat newspaper in their March 1947 edition when they revealed that he had been appointed as the playing manager of the Orangeville Tigers at the tender age of 21. By then, Willie was called “Curly” because of his processed hair, like Nat King Cole. His inherent talent for instructing and guiding became evident as he visited local schools, imparting the fundamentals of baseball to the younger generation.

By July 1947, just three months after Jackie Robinson broke the colour barrier and entered the major leagues by signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Williams was put on the MLB radar, according to The Press Box’s sports columnist Jake Penland:

But it was his signing with the famous Newark Eagles of the Negro National League in 1948 that kicked things into high gear for Curly. In a letter addressed to Orangeburg Tiger coach Paul Webber, Williams shared his enthusiasm at being chosen as their shortstop. The note concludes with the columnist expressing pride that a member of Orangeburg who “grew up on the tough side of the railroad track” is now playing in the Negro Leagues.

Williams became the Eagles’ shortstop, playing in Newark following Houston and New Orleans as the team was relocated. In an interview with Brent Kelly for his book Voices from the Negro Leagues – Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts, Williams discussed his experiences playing on the road in the rough racial climate of the Jim Crow era:

“Some places you got treated well and some places it was just ridiculous. You have to just take those things, you know – hear it then don’t hear it.” (Kelley, Pg 178)

In 1950, as a member of the Houston Eagles, he was selected to play in the Negro League’s East-West All-Star Game at Comiskey Park in Chicago. (Cieradkowski)

A few months later, Williams attracted more major league interest during winter ball in Puerto Rico, particularly after a remarkable seven-day stretch where he hit six home runs. The Chicago White Sox took notice, and the almost six foot, 175-pound shortstop was assigned to Colorado Springs Sky Sox in the Western League, impressing with a .297 batting average. He and his fellow African American players experienced racial discrimination, which led Williams to leave the White Sox and return to the Negro League Eagles, now in New Orleans. Eventually persuaded to rejoin the White Sox system, he began the 1952 season with Toledo.

Williams again faced racial challenges during spring training in Avon Park, Florida, which he shared at a Newark Eagle tribute day in September 2007. Williams, who reached for a handkerchief during the tribute to dry his eyes, vividly recalled the poignant imagery of the physical barrier that separated him from his teammates during dinner, a painful testament to the segregation that defined those times:

“I went to spring training in Avon Park with the Colorado team. They had a place with a preacher for me to stay. [There was] a café with my table in the kitchen. Every time that door swung open, all I could see [was] all my teammates out there. They had a table for me set up in the kitchen. That hurt. And what hurt so bad, they had a Mexican guy for my roommate; he could go in there. At night, I just cried and it made me feel better…” (Diunte)

Williams continued his baseball journey despite these obstacles, making significant contributions in various leagues. Williams, in the interview with Kelly, concluded the major league missed out on hiring African American players:

“That’s just the way it was back then. It shouldn’t have been that way, but I’ll tell you one thing – they missed out on some of greatest ballplayers ever lived. I seen some ball players, man. I used to just sit on that bench and here I am a young man, these guys out there 40 years old and I can’t move ’em! [Laughs] I almost cried. These guys were playing like they were 15 years old.” (Kelly, Pg. 180)

Williams played in the Man-Dak (Manitoba Dakota) league for one year, in 1953, with the Carman Cardinals, then jumped back to the Dominican and finally with the Birmingham Black Barons in 1954, where he remained among the league’s top sluggers.

He decided to give Canada another try, and the story goes Williams got in his car with his family and headed north from South Carolina to Canada in 1955 for another trial run. During his journey, racism once again reared its ugly head, and numerous stores refused to sell him diapers for his child, prompting frustration and anger. However, he held onto the hope that things would improve—indeed, they did.

Curly & the Lloydminster Meridians

Playing in the United States was taking an emotional toll on Williams, having to face daily racism and exclusion off and on the diamond. In Lloydminster, he found a peace he had never felt before. He was treated with dignity and respect by a supportive and accepting community, even if financial rewards may have been modest compared to what he was used to:

“It was awful. I cried so much when I was in professional baseball, I tell you. (In Canada) we were treated so well up there that’s why I stayed up there so long … We had so much fun there and everybody was accepted, you know, didn’t have problems going any place we wanted to eat. Just wonderful people. May not have made a whole lot of money but people were excited and they enjoyed you and would invite you to their homes.” (attheplate.com)

Jay-Dell Mah, that young bat boy who shined Williams’ shoes and washed his socks, had no idea about Curly’s life in the United States. Shielded by Canadian societal norms, Williams’ stories seemed “unfathomable.” Mah remembers hearing Williams talk about segregation:

“…couldn’t eat at the same restaurants as their teammates, even stay in the same hotels. Couldn’t use the same public water fountain as the whites in the community. Couldn’t sit at the counter in the department store deli. Even the black spectators at the games sat in their own special section… He said they had become used to the practice of stepping off the sidewalk, onto the street, if white pedestrians were coming toward them. They didn’t even talk about lynchings…” (Mah)

It was sobering for Mah to hear about the realities beyond his sheltered youth: “If only … we’d been taught a little of this in school, some of us would have been in a better position to understand, empathize, and help make change decades earlier.” Mah refers to the treatment of the people of African descent as well as others who suffered in Canada, such as the survivors of Indigenous Residential Schools and Japanese internment camps in British Columbia during the Second World War.

For Williams, Lloydminster baseball was the great equalizer where he played on an integrated team with whites; skin colour didn’t matter, just as long as the player had skill and talent. For nearly a decade, he was one of the league’s best players and the best person anyone could meet. The Meridians’ owner, Slim Thorpe, bestowed the nickname “Mr. Baseball” to Williams. Using such a title often signifies a high level of respect and recognition for an individual’s impact on the sport, whether it be through exceptional performance, leadership, or contributions to the baseball community:

“Curly Williams was one of the finest gentlemen that I ever met. (He) was always helping the kids. We’d get these young college boys, and Curly was in there talking to them, showing them how to do it. Curly was a Triple-A ball player, and he stayed with us as long as our league lasted.” (Slim Thorpe, in 75 Years of Sport & Culture in Lloydminster via attheplate.com)

Williams’ performance in 1954 was top-notch: “In his first season in Lloydminster, he hit .280 and, as a third baseman, led the league in fielding. The following year, he was the team’s leading hitter with a .314 average, 7 homers and 45 RBI. Again, he’d lead the league in fielding, this time at shortstop.” (attheplate.com)

1961

During the summer of 1961, a significant shift occurred for Curly Williams and the Meridians when he assumed the manager role, taking over from Cliff Pemberton, who had fractured his hand. This change marked a pivotal moment in Williams’ leadership as he steered the team through significant victories. On June 23, the Meridians emerged as winners in a Western Canadian Baseball League double-header against the Lethbridge White Sox, clinching victories with 12-11 and 4-3 scores. Notably, Williams showcased his batting prowess by slamming a bases-empty homer in the second game’s first inning and later drove in the winning run for Lloydminster in the 10th. In true leadership fashion, Williams directed the team to 25 wins in 32 games in his first full month as manager.

However, the summer also brought more unexpected challenges. On July 10, the Lloydminster Meridians folded, leading to the Western Canadian Baseball League taking ownership and relocating the franchise to Medicine Hat. Despite the team’s upheaval, Curly remained a candidate to stay on as a player-manager. By July 14, Williams, determined to prove the team’s resilience, delivered a standout performance, blasting an inside-the-park home run and contributing to the Meridians’ 5-3 victory over the Edmonton Eskimos. The summer continued with success for the team as, on July 28, they secured a triumph in the Lacombe Tournament, defeating the Lethbridge White Sox 3-2 and earning the Western Canadian Baseball League $1,100 in prize money:

“If you had to pin-point Medicine Hat’s main reason for success you would have to put the finger on player manager Curly Williams, second base. His leadership keyed his club up, as he hit three for four in the final and scored two of the three runs. Earlier he had hit three for four, a double, triple and homer, as his boys side lined the Eskimos.

That made it quite a day for Curly, but was only part of the story as he was a defensive star, too…Meridians went ahead 1-0 in the second when three consutive singles loaded the bases, and Williams was safe at home when catcher John Bartholamew dropped the ball when Curly slid into him trying to beat out Stan Busch’s perfect peg from left field.” (July 28, 1961, Pg. 8, Edmonton Journal)

By July 31, the Medicine Meridians whipped the Edmonton Eskimos 16-4 to win the 11th annual Lethbridge Rotary International tournament. (attheplate.com)

A final blow to Williams was when the Medicine Hat Meridians folded after only a few weeks. Once again, he and other Meridians were transferred to the Lethbridge White Sox just in time to participate and win the Western Canadian League championship. Perhaps an additional twist of irony from his not-so-nice experience with the Chicago White Sox franchise. A true leader, Williams carried the players through three transfers and continued to inspire his men to prevail against all odds.

After 1961, Williams returned to Lloydminster to head up the newly formed team, the Green Caps, in the Northern Saskatchewan Baseball League. Curly retired after 20 years in 1963 and went out with a .391 average.

Curly’s life outside of baseball

Williams returned to the United States and became a pathology assistant at the Sarasota County Medical Examiner’s Office for over 30 years. Never forgetting his roots and baseball, he and his wife Annette established the Curly Williams Foundation to grant college scholarships to underprivileged students. The Sarasota City Council proclaimed a “Curly Williams Day” in 1997. In 2012, Williams was inducted into the Saskatchewan Baseball Hall of Fame.

His legacy

The story of Willie “Curly” Williams, known as Mr. Baseball of Western Canada from 1953 to 1963, unfolds as a captivating journey filled with triumphs, challenges, and enduring contributions to the sport and community. Williams, a seasoned Negro League player, found refuge and acceptance in the warm embrace of Western Canadian baseball fans, particularly in Lloydminster, a border city he called home for eight exciting summers. The nickname “Mr. Baseball,” bestowed upon him by Meridians owner Slim Thorpe, encapsulates the profound impact Williams had on the baseball community, not only for his exceptional performance on the field but also for his leadership and mentorship off it.

Williams faced the harsh realities of racial discrimination in the Jim Crow era, both in the United States and during his journey through the baseball circuits. Despite these challenges, he found solace and a sense of belonging in the Canadian baseball landscape. His experiences shed light on the stark contrast between the oppressive conditions he faced in the U.S. and the welcoming, inclusive community he encountered in Western Canada.

The summer of 1961 is a significant chapter in Williams’ career, marked by unexpected twists and turns. Williams displayed resilience and leadership from assuming the manager role for the Lloydminster Meridians to the team’s relocations and eventual triumph in the Western Canadian League championship. His ability to inspire his teammates through three transfers, unforeseen challenges, and triumphs showcases the true essence of a mentor and coach.

Reflecting upon Williams’s life story, which transcends racial boundaries and leaves an enduring legacy of resilience, leadership, and community service, it’s essential to acknowledge the historical neglect of our immigrants and Indigenous peoples within Canada. As we celebrate Black History Month, it’s a reminder to examine Canada’s own history, recognizing our own racism and the struggles of those who have contributed to the nation’s diverse tapestry.

Thank Yous

Many thanks to Mr. Jay-Dell Mah, who continues to inspire me to share as many stories as possible about early Western Canadian Baseball history. To Joe and the rest of the Alberta Dugout Stories team, thank you for highlighting these important ball players who contributed so much to Western Canadian Baseball history.

About the Author

Robyn Jensen is a storyteller, baseball historian, curator, and artist who has lived in the community of Indian Head, Saskatchewan, for almost 20 years. Her involvement in the local museum led her to research and create an exhibit for The Indian Head Rockets (all African American and Cuban Baseball Teams 1950-54). Inspired by that work, she has returned to university for a master’s degree in Media and Artistic Research, researching racism in newspapers and writing a thesis using the 1952 Rosetown Baseball Riot as the catalyst. Needing an outlet to share the additional stories she uncovered along the way, she created a blog called Home Runs & Dirt Roads – Stories of Baseball in Saskatchewan (homerunsdirtroads.ca). You can also find her on Instagram at @homerunsdirtroads.

Sources

Baseball In Living Color. “#157 – Willie ‘Curley’ Williams.” YouTube, 2 Dec. 2021, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ysyFCOuX6yc.

Cash to the Winners…Rotary Baseball Tournament. Lethbridge Herald, 6 July 1961, p. 6.

Cieradkowski, Gary Joseph. The Infinite Baseball Card Set. infinitecardset.blogspot.com/search/label/Curly%20Williams.

“Curley Williams Stats, Height, Weight, Position, Rookie Status and More | Baseball-Reference.com.” Baseball-Reference.com, http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/w/willicu01.shtml.

Curly Williams…has His Medicine Hat Meridians Hitting Fast Clip in the WCBL. Star Pheonix, 1 Aug. 1961, p. 10.

Curly Williams…waves Big Bat. The Calgary Herald, 28 July 1961, p. 15.

Diunte, N. Negro League Legend Willie “Curly” Williams Left a Lasting Impact on Many. http://www.baseballhappenings.net/2011/08/negro-league-legend-willie-curly.html.

Kelley, Brent P. Voices From the Negro Leagues: Conversations With 52 Baseball Standouts of the Period, 1924-1960. 1997, ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA4034290X.

Negro League Roots in Columbia | Richland Library. 3 Feb. 2021, http://www.richlandlibrary.com/blog/2021-02-03/negro-league-roots-columbia.

Negro Leagues Baseball eMuseum: Personal Profiles: Willie Williams. nlbemuseum.com/history/players/williamsw.html.

“Orangeburg Tigers Player Lands Spot With Newark Eagles.” Alabama Tribune, 21 May 1948, p. 7.

Penland, Jake. “The Press Box.” The State, 14 July 1947, p. 11.

Profile Curly Williams. http://www.attheplate.com/wcbl/profile_williams_curly.html.

Swanton, Barry, and Jay-Dell Mah. Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary 1881-1960. McFarland, 2009.

“Tigers to Play Tuskegee Here.” The Times and Democrat, 20 Mar. 1947, p. 7.

One thought on “Willie “Curly” Williams – Mr. Baseball of Western Canada”